Add your promotional text...

Are Our Fruits and Vegetables Less Nutritious Than They Used To Be?

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Bhardwaj RL, Parashar A, Parewa HP, Vyas L. An Alarming Decline in the Nutritional Quality of Foods: The Biggest Challenge for Future Generations' Health. Foods. 2024 Mar 14;13(6):877. doi: 10.3390/foods13060877. PMID: 38540869; PMCID: PMC10969708. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

11/21/20253 min read

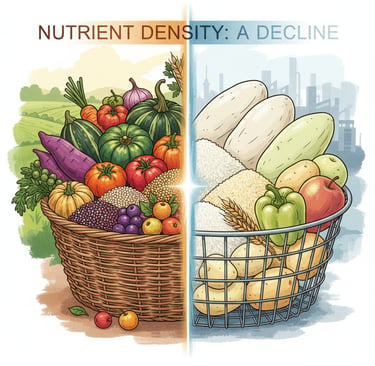

Have you ever wondered if the apple you eat today is as nutritious as the one your grandparents ate? It’s a concerning question, and according to a growing body of scientific evidence, the answer is likely no. Over the last 60 years, researchers have documented an alarming decline in essential minerals, vitamins, and other beneficial compounds in many of our staple fruits, vegetables, and crops. While we're producing more food than ever before, we're facing a paradox: we are becoming overfed yet undernourished. Let's explore why our food is changing and what we can do about it.

The Hidden Hunger: A Global Problem

Globally, over two billion people suffer from "hidden hunger," a deficiency in crucial micronutrients like iron, zinc, vitamin A, and iodine. This isn't just a problem for developing nations; it affects everyone. Malnutrition is a leading cause of preventable health issues, stunting physical and mental growth in children and contributing to millions of premature deaths annually.

Since the "Green Revolution" of the mid-20th century, farming has become incredibly productive. We've mastered techniques to increase yield with intensive farming, chemical fertilizers, and high-yielding crop varieties. Yet, while our plates are full, the nutritional density of what's on them has been steadily dropping. Studies show that a wide range of popular fruits and vegetables have lost a significant percentage of their minerals and vitamins over the last 50-70 years. For example, researchers have documented significant declines in iron, copper, magnesium, and calcium in various foods, with some nutrients falling by as much as 50-75% or more.

What’s Causing This "Nutrient Dilution"?

The decline isn't due to one single cause but a combination of factors related to how we've changed our food systems.

Breeding for Yield, Not Nutrition: For decades, the primary goal of plant breeding has been to create varieties that grow bigger, faster, and are more resistant to pests. The focus has been on yield (quantity) over nutritional content (quality). This often creates a "dilution effect" – the plant produces more carbohydrates (sugars and starches), but the concentration of minerals and vitamins gets spread thin.

A Shift in Our Diets: We've moved away from diverse, traditional diets. Nutrient-dense crops like millets (sorghum, pearl millet, etc.), which were once staples, have been replaced by a few high-yield but often less nutritious cereals like modern wheat, rice, and maize. A study of tribal farmers in Rajasthan, India, for example, showed that wheat consumption increased by a staggering 5,500% over 60 years, while consumption of highly nutritious minor millets plummeted by over 98%.

Degraded and Depleted Soils: Modern farming practices have taken a toll on our soil. The overuse of synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and intensive tillage has disrupted the delicate balance of soil life. Healthy soil is a living ecosystem teeming with microbes that help make nutrients available to plants. When soil biodiversity and organic matter decline, the soil's ability to nourish the crops grown in it is compromised. Our arable land is literally becoming deficient in key minerals like zinc, iron, and boron.

Rising Atmospheric CO2: A surprising culprit is the increasing level of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere. While CO2 helps plants grow bigger through photosynthesis (the "fertilization effect"), studies show it also reduces the concentration of key nutrients. Plants grown under elevated CO2 often contain less protein, zinc, and iron, and fewer vitamins. Essentially, they become "junk food" plants—bigger, but less nutritious.

The Path Forward: Restoring Nutrient Density to Our Food

The good news is that we can reverse this trend. The solution requires a multi-faceted approach focused on restoring the health of our entire food system, from the soil up.

Reviving Traditional Foods: We need to bring back nutrient-rich traditional crops like millets and diverse local fruits and vegetables. These "future-smart foods" are not only packed with minerals and vitamins but are often more resilient to climate change. Recognizing this, the UN declared 2023 the "International Year of Millets" to promote their cultivation and consumption.

Adopting Organic & Regenerative Farming: Shifting away from heavy reliance on chemical inputs towards organic and regenerative practices is crucial. These methods focus on building soil health, which directly translates to more nutrient-dense food. Studies consistently show that organically grown produce often contains higher levels of vitamin C, iron, magnesium, and health-promoting antioxidants.

Improving Soil Biodiversity: We must treat soil as a living ecosystem. Practices like using cover crops, crop rotation, and reducing tillage can restore the beneficial microbial communities (like PGPB, which we've discussed before!) that are essential for nutrient cycling and helping plants access minerals from the soil.

Breeding for Quality: The focus of plant breeding needs to expand beyond just yield. We need to develop and promote crop varieties that are not only productive but also biofortified—naturally bred to contain higher levels of essential nutrients like zinc, iron, and vitamins.

Smarter Post-Harvest Handling: Nutrients can also be lost after food is picked. Improving how we store, process, and cook our food can help preserve its nutritional value from farm to table.

Ultimately, the health of our future generations depends on the nutritional quality of the food we grow and eat. By reframing our agricultural goals to prioritize both quality and quantity, we can work towards a future where everyone is not just fed, but truly nourished.