Add your promotional text...

Beyond Magic Microbes: Why Your Soil's "Locals" Call the Shots

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Wang Z, Fu X, Kuramae EE. Insight into farming native microbiome by bioinoculant in soil-plant system. Microbiol Res. 2024 Aug;285:127776. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127776. Epub 2024 May 20. PMID: 38820701. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

12/12/20254 min read

For years, we've heard about the promise of "biofertilizers" and "bioinoculants" – pouring helpful, lab-grown microbes onto our fields to boost crops and improve soil. It sounds simple, like adding a super-powered probiotic to your garden. But as many farmers and scientists have discovered, the results can be frustratingly unpredictable. Why does the same "magic microbe" work wonders in one field and completely fail in another? A growing body of research points to a powerful, often-overlooked factor: the existing "locals" – the native microbiome already living in the soil.

The Complicated Social Life of Soil Microbes

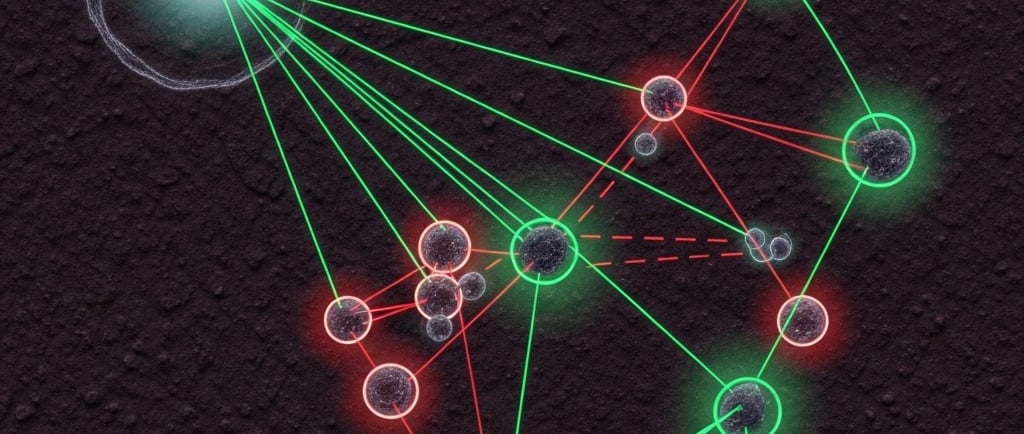

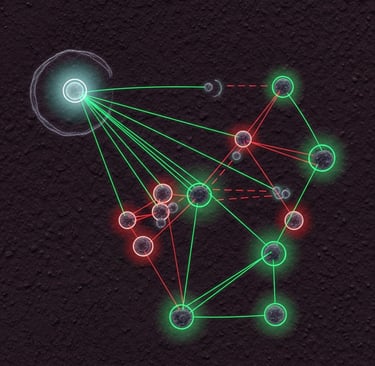

Think of your soil as a bustling, crowded city. It's already packed with billions of native microorganisms, each with its own job, food source, and network of allies and rivals. When we introduce a new beneficial microbe (BM), it's like a newcomer arriving in town. What happens next is a complex social drama:

Will they be accepted? Sometimes, the locals are welcoming, and the newcomer thrives, adding its unique skills to the community.

Will they be outcompeted? Often, the native microbes are so well-adapted to their home that the newcomer can't find food or space and simply fades away.

Will they start a fight? The newcomer might compete for resources, leading to antagonism.

Or will they inspire the locals? In a fascinating twist, sometimes the introduced microbe doesn't do much itself but acts as a catalyst, waking up and activating the native microbes to do the beneficial work!

The old approach was to focus only on the newcomer. The new approach, what some are calling "microbiome breeding," is about understanding this entire social network. The goal isn't just to add a good microbe, but to steer the entire microbial community in a helpful direction.

Native vs. Non-Native: Who Performs Better?

A key question is where these beneficial microbes come from. Are "exotic" microbes from a commercial lab better than "native" ones isolated from the local soil itself?

Research often shows that native microbes perform as well as, or even better than, commercial strains. This makes sense – they are already perfectly adapted to the local soil chemistry, climate, and plant life. They're the true locals.

However, commercial microbes are often bred for broad adaptability. The challenge is that when an exotic microbe enters a new soil, it's essentially a microbial invasion. It might survive for a while if it's given a food source (like organic amendments), but it frequently gets outcompeted by the established residents. In contrast, re-introducing a supercharged native microbe is more like reinforcing a friendly population, though even they can struggle to regain dominance. The unpredictable outcome of this interaction is one of the biggest challenges in making biofertilizers reliable.

Unlocking Potential: Finding the "Helpers" and Muting the "Inhibitors"

The native soil community isn't just a faceless crowd; it contains specific players.

"Helpers": These are native microbes that synergize with the introduced ones. They might help the newcomer establish itself or have complementary skills that, when combined, provide a huge boost to soil fertility or plant health. The goal of microbiome breeding is to identify and encourage these helpers.

"Inhibitors": These are the subtle rivals. They might outcompete the introduced microbe for food, produce compounds that inhibit it, or simply occupy the same niche, preventing the newcomer from gaining a foothold. These inhibitors are harder to spot but are a key reason why beneficial effects can be short-lived.

Effective "microbiome farming" means creating conditions that favor the helpers while discouraging the inhibitors.

The Persistence Problem: Why a Single Dose is Rarely Enough

One of the biggest hurdles is that the benefits of bioinoculants are often temporary. The introduced microbes frequently fail to establish a lasting population. Studies show that effects can disappear in as little as 45 days. This is why a single application rarely works long-term and why many studies that only sample once miss the full story.

The success and persistence of an introduced microbe depend on a huge range of factors: the soil type, the existing microbial diversity (it's often easier for newcomers to establish in less diverse, "disturbed" soils), the plant host, and even the application method (solid forms often last longer than liquid ones). To truly engineer a soil microbiome, we need to monitor these dynamic changes over time, not just at a single snapshot.

The Path Forward: A Smarter Approach to Soil Health

Realizing the full potential of beneficial microbes requires a shift in thinking. Instead of just dropping in a single "hero" microbe, the future lies in:

Understanding the Team: We need better tools (like advanced modeling) to identify the key players – the "helpers" and "inhibitors" – already in the soil.

Creating Favorable Conditions: This means optimizing our farming practices (like using specific organic amendments or crop rotations) to selectively encourage the microbes we want.

Building Smart Teams (Consortia): Co-inoculating with multiple beneficial strains that have different functions (some for growth, some for disease control) can be more effective and resilient than using just one.

Optimizing Application: Researching the best timing, density, and formulation (e.g., microencapsulation to protect microbes) is crucial for helping them survive and thrive.

Ultimately, the goal is to move from simply inoculating to actively engineering and steering the entire soil microbiome. By understanding the complex interdependencies between the microbes we add, the microbes that are already there, and the environment they live in, we can unlock the full, sustainable power of our soil's natural bioresources.