Add your promotional text...

Beyond N-P-K: The Microbial Key to Sulfur, the Fourth Major Nutrient

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Chaudhary S, Sindhu SS, Dhanker R, Kumari A. Microbes-mediated sulphur cycling in soil: Impact on soil fertility, crop production and environmental sustainability. Microbiol Res. 2023 Jun;271:127340. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2023.127340. Epub 2023 Feb 24. PMID: 36889205.. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

10/20/20253 min read

When we think about feeding plants, nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) usually steal the spotlight. But there's a fourth major nutrient working tirelessly behind the scenes: sulfur (S). Essential for everything from protein synthesis to creating the flavors in onions and mustard, sulfur is a cornerstone of plant health. But there's a growing problem—our soils are becoming increasingly deficient in it. Fortunately, nature has its own solution: an army of microscopic allies in the soil that can unlock this vital nutrient.

The Growing Problem of Sulfur Deficiency

Sulfur isn't just a plant nutrient; it's fundamental to all life. In plants, it's a key component of essential amino acids (the building blocks of proteins), oils, and vitamins. When plants don't get enough sulfur, the consequences are stark: young leaves turn yellow, growth is stunted, photosynthesis slows down, and crop yields plummet. Oilseed crops like canola and pulses are especially thirsty for sulfur.

So, why are our soils running low? Several factors are at play:

Cleaner Air (An Unexpected Consequence): Decades ago, industrial pollution deposited significant amounts of sulfur onto the land via acid rain. With cleaner air regulations (a major environmental win!), this unintentional "fertilization" has largely stopped.

Modern Fertilizers: Many modern, high-concentration fertilizers focus on N-P-K and contain little to no sulfur, unlike older fertilizers like single superphosphate.

High-Yielding Crops: Today's high-performance crop varieties are incredibly productive, but they also pull more nutrients, including sulfur, out of the soil with every harvest.

This has created a "sulfur gap" in many agricultural regions worldwide. While we can apply sulfur fertilizers, their overuse, like other agrochemicals, can have negative environmental impacts, contributing to soil and water pollution. This dilemma has pushed scientists to look for a more sustainable, natural solution.

Enter the Microbial Solution: Sulfur-Cycling Superstars

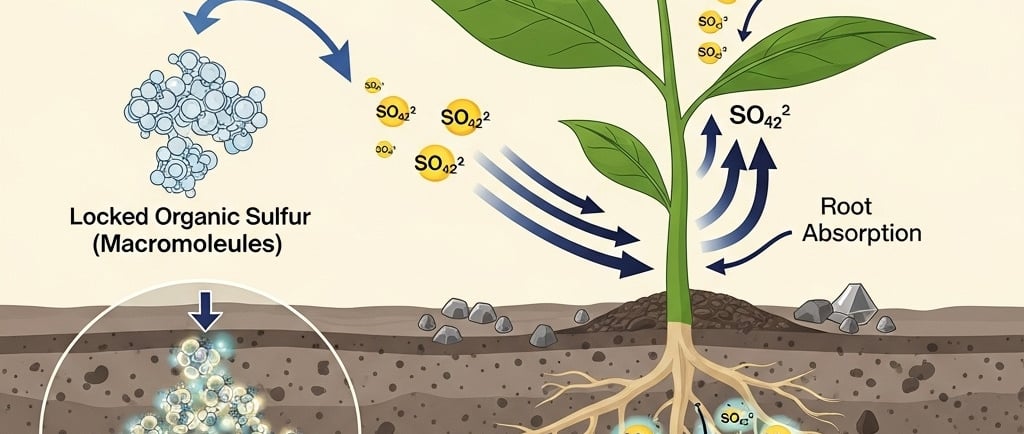

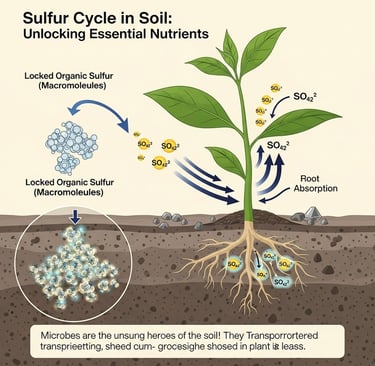

The answer lies right beneath our feet, in the diverse world of soil microbes. The vast majority of sulfur in the soil is locked up in organic forms that plants can't use. Plants need sulfur in a simple, inorganic form called sulfate (SO₄²⁻). This is where a special group of microorganisms comes in.

These beneficial microbes, particularly Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria (SOB), act as nature's recyclers. They have the unique ability to take various unavailable forms of sulfur and transform—or "oxidize"—them into the plant-ready sulfate. This process, part of the natural biogeochemical sulfur cycle, is crucial for maintaining soil fertility.

How Do These Microbes Help? (The Direct and Indirect Benefits)

The magic of these microbes goes far beyond just providing sulfate. When applied as "biofertilizers" or "microbial inoculants," they support plant growth in numerous ways:

Direct Benefits (Nutrient & Hormone Support):

Nutrient Conversion: Their primary job is converting sulfur into sulfate.

Acidification & Nutrient Release: The process of sulfur oxidation often produces small amounts of acid, which can slightly lower the soil pH in the immediate root zone. This is a good thing in many soils, as it helps to unlock and make other vital nutrients like phosphorus and iron more available to the plant.

Hormone Production: Like other plant-growth-promoting microbes, many SOB can produce plant hormones (like auxins) that encourage stronger and more extensive root growth.

Indirect Benefits (Plant Protection & Stress Relief):

Disease Suppression: A lower pH around the roots can inhibit the growth of certain soil-borne fungal pathogens.

Stress Amelioration: Some of these microbes help plants better tolerate abiotic stresses like salinity and drought.

Symbiotic Partnerships: In legumes, adequate sulfur is critical for the nitrogen-fixing process in root nodules. By providing sulfur, these microbes indirectly boost nitrogen fixation.

Field studies have shown impressive results. Inoculating crops like onions, wheat, and mustard with SOB has led to significant yield increases, improved nutrient uptake, and healthier plants. When combined with other beneficial microbes, like nitrogen-fixers or phosphate-solubilizers, the synergistic effects can be even greater, demonstrating the power of a healthy, diverse soil microbiome.

Harnessing the Power of Sulfur Microbes

The use of SOB as biofertilizers offers a promising, eco-friendly way to tackle sulfur deficiency, reduce our reliance on chemical fertilizers, and support sustainable agriculture. By enriching the soil with these specialist microbes, we can help restore a natural and vital nutrient cycle.

However, the path to widespread use requires more research. Scientists are working to identify the most effective microbial strains for different crops and soil types, develop stable formulations for farmers to use, and ensure they perform reliably in real-world field conditions.

The future of farming may well depend on our ability to work with nature. By understanding and harnessing the power of these sulfur-cycling microbes, we can improve soil fertility, boost crop production, and take a significant step towards a more sustainable food system.