Add your promotional text...

Beyond Superbugs: Why Teamwork is Key to Cleaning Up Herbicides

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Pileggi M, Pileggi SAV, Sadowsky MJ. Herbicide bioremediation: from strains to bacterial communities. Heliyon. 2020 Dec 24;6(12):e05767. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05767. PMID: 33392402; PMCID: PMC7773584. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

12/17/20253 min read

The Double-Edged Sword of Modern Farming

To feed a growing world, modern agriculture relies on powerful tools, and herbicides are one of the most common. These chemicals are designed to target weeds, clearing the way for our crops to thrive. But this efficiency comes at a cost. The widespread use of herbicides has led to a cascade of unintended consequences: from the rise of resistant "superweeds" to the contamination of our soil, rivers, and groundwater.

These chemical residues don't just sit there; they can disrupt the delicate balance of soil microbial communities, affect the health of non-target organisms (from tiny invertebrates to fish), and persist in the environment for years. For decades, a seemingly simple solution has been pursued: find a single, powerful microbe that can "eat" a specific herbicide and release it into the environment to clean up the mess. This process is called bioremediation.

The problem? This "lone wolf" approach has often been disappointing. A superstar strain that works wonders in a clean lab environment often fails in the complex, competitive, and stressful conditions of a real field. To truly solve our herbicide problem, we need to think less about individual microbes and more about the power of the entire microbial community.

First, Survive. Then, Degrade.

Before a microbe can even begin to break down a herbicide, it has to survive being exposed to it. Many herbicides are designed to disrupt cellular processes and, in doing so, create a burst of damaging molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS). This "oxidative stress" is harmful to all living cells, not just weeds.

To cope, microbes have evolved a sophisticated toolkit of antioxidant defenses – a complex system of enzymes that act like cellular bodyguards to neutralize these harmful ROS. This defense system isn't specific to herbicides; it's a general stress response. This means that exposure to herbicides can sometimes trigger broader changes in microbes. For instance, some studies have shown that exposure to certain herbicides can unexpectedly make bacteria more resistant to antibiotics by activating these general defense and efflux pump systems!

The Power of Teamwork: Why Microbial Consortia Work Better

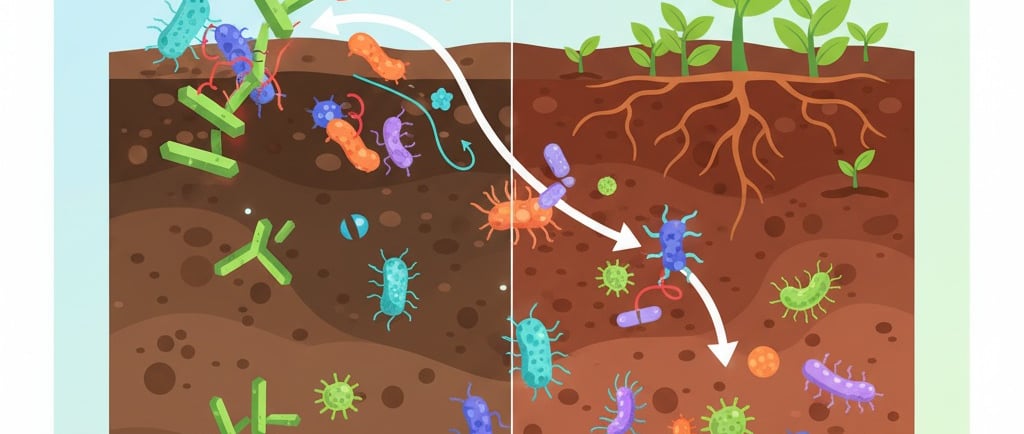

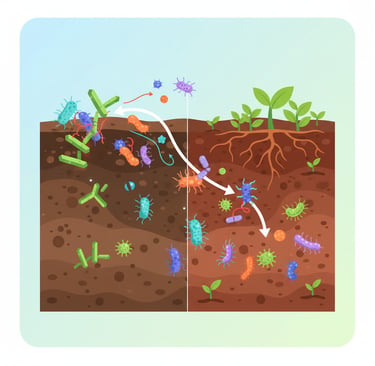

The real world of soil and water isn't a collection of individual microbes working alone; it's a bustling metropolis of diverse communities, often living together in structured biofilms. Within these communities, microbes "talk" to each other using chemical signals (quorum sensing) and work together in complex ways.

This is where the single-strain approach to bioremediation often falls short. Breaking down a complex chemical like an herbicide is rarely a one-step job. It's often a multi-step process, like an assembly line:

Microbe A might perform the first step, breaking the herbicide into a simpler intermediate compound.

Microbe B, which can't touch the original herbicide, might be an expert at consuming the intermediate from Microbe A.

Microbe C might then take the waste product from Microbe B and finish the job, fully mineralizing the compound into harmless components like carbon dioxide and water.

This metabolic teamwork, or synergy, is incredibly efficient. A community (or consortium) of different microbes working together can often degrade a pollutant much faster and more completely than any single strain could on its own. They share the workload, prevent the buildup of toxic intermediates, and create a more resilient system.

Unlocking the Secrets with "Omics"

So, how do we study and harness the power of these complex microbial teams? This is where modern "omics" technologies come in. These high-throughput techniques allow scientists to look beyond single genes or single microbes and get a big-picture view of the entire community:

Metagenomics: Sequencing all the DNA in a sample to see who is there and what genetic tools they possess.

Metatranscriptomics: Analyzing all the RNA to see which genes are actually being used or are "turned on" by the community in response to a herbicide.

Proteomics & Metabolomics: Studying all the proteins and metabolic byproducts to understand the community's actual functions and chemical transformations in real-time.

Using these powerful tools, scientists can move beyond just isolating one "superbug." They can now identify the key players in a consortium, understand how they communicate and share metabolic pathways, and design smarter bioremediation strategies. The goal is to assemble or encourage "smart swarms" of microbes specifically tailored to work together to eliminate specific pollutants efficiently and safely.

The Path Forward: A Global Challenge

The future of cleaning up herbicide contamination lies in embracing this community-based approach. By understanding the intricate dance of microbial teamwork, we can develop far more effective and sustainable bioremediation solutions.

However, a significant challenge remains. These advanced "omics" technologies are expensive and require sophisticated bioinformatics to analyze the massive amounts of data they generate. This creates a potential gap, as many developing nations that are major food producers and heavy consumers of pesticides may not have easy access to these cutting-edge tools. Ensuring that this knowledge and these technologies are shared globally is paramount to achieving truly sustainable agriculture and protecting our shared environment from the unintended side effects of our quest to feed the world.