Add your promotional text...

Saving Thirsty Crops: How Biochar, Bacteria, and Cellular Recycling Could Secure Our Food

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Koyro HW, Huchzermeyer B. From Soil Amendments to Controlling Autophagy: Supporting Plant Metabolism under Conditions of Water Shortage and Salinity. Plants (Basel). 2022 Jun 22;11(13):1654. doi: 10.3390/plants11131654. PMID: 35807605; PMCID: PMC9269222. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

2/2/20264 min read

The Challenge: A Thirsty Planet and Hungry Population

Our world faces a monumental challenge: the human population is growing, and so is our demand for food, fuel, and materials derived from plants. Yet, the very foundation of our food system—fertile land and sufficient water—is under increasing strain. Global climate change is making extreme weather like drought more common. At the same time, soil quality is degrading, and salinization (the buildup of salt in soil) is rendering vast tracts of farmland unproductive.

By 2050, it's estimated that half of all arable land could be impacted by salinity, and water shortages have already been shown to slash yields of critical crops like wheat and maize by 20-40% worldwide. If we need to nearly double food production to meet future demands, how can we do it on a planet where the conditions for growth are getting tougher?

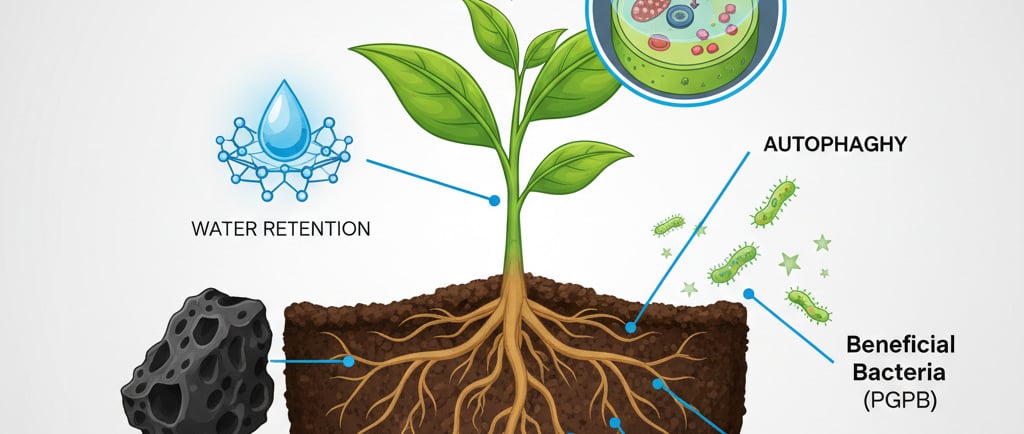

For years, scientists have focused on breeding more stress-resistant crops. While progress has been made, we now understand that a plant's success isn't just about its genes; it's deeply connected to its environment. This has sparked immense interest in two powerful tools that work with nature to improve the soil and support plants directly: biochar and plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB). Let's explore how they help and connect them to a fascinating internal process plants use to survive: autophagy.

Part 1: Bolstering Defenses from the Ground Up

Before a plant even senses stress, its resilience is determined by the quality of its soil.

Biochar: The Soil's Super-Sponge

Biochar is a charcoal-like substance made by heating organic material (like wood or crop waste) in a low-oxygen environment. When added to soil, it acts like a high-performance sponge. Its incredibly porous structure enhances the soil's ability to hold onto both water and nutrients, releasing them slowly to plant roots.

This creates a more stable and reliable environment. Instead of experiencing jarring cycles of drought and flood, or nutrient feast and famine, plants get a more even supply. The result? Plants grown in biochar-amended soil are better buffered against sudden dry spells and can maintain healthier growth. Research shows this effect is most dramatic in poor or marginal soils. Furthermore, biochar provides a fantastic habitat for beneficial soil microorganisms, creating a synergistic effect.PGPB: The Plant's Microbial Bodyguards

The soil is teeming with life, and a special group of bacteria known as Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB) form a close partnership with plants. Living on and inside roots, they act as tiny support systems. They can produce plant hormones to encourage root growth, unlock nutrients like phosphate and nitrogen that are otherwise inaccessible, and even help plants manage internal stress signals. We've explored PGPB in detail before, but their role in a holistic solution alongside biochar is critical. When PGPB are present, especially in biochar-rich soil, plants are better equipped to handle stress from the get-go.

Part 2: The Internal Response - Cellular Recycling to the Rescue

Even with soil support, plants will face stress. When drought or salinity hits, it's not just about a lack of water; it's a crisis at the cellular level. Photosynthesis—the process of turning light into energy—gets disrupted. When a plant can't use the light energy it absorbs because growth has slowed, that excess energy can create harmful molecules called Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), which are like cellular rust, damaging vital components.

To survive this, plants have an incredible, built-in recycling system called autophagy (literally "self-eating").

Think of autophagy as the cell's master cleanup crew and recycling program. When a plant is under stress and resources are scarce:

It Removes the Junk: Autophagy targets and breaks down damaged or unnecessary components within the cell, like malfunctioning proteins or organelles damaged by ROS.

It Recycles Building Blocks: The raw materials from this breakdown (like amino acids) are then released back into the cell to be used for building new, essential components or for providing energy.

This recycling process is a game-changer during stress. It allows a plant to reallocate resources, repair damage, and maintain essential functions for a longer period, giving it a better chance to survive until conditions improve.

Connecting It All: How Hormones and Soil Helpers Influence Autophagy

The activity of this cellular recycling is tightly controlled by a network of signals, including plant hormones like ABA and ethylene. When a plant senses drought, hormone levels change, which in turn can ramp up autophagy to help the cell cope.

This is where biochar and PGPB come back into the picture. By creating a healthier soil environment, they reduce the initial intensity of the stress the plant experiences. PGPB can also influence the plant's hormone levels, helping to fine-tune its stress response. For instance, some PGPB help lower stress-induced ethylene, which might prevent autophagy from going into a self-destructive overdrive.

In essence, soil amendments don't just provide a buffer; they help the plant manage its internal stress response more effectively, potentially making processes like autophagy a life-saving tool rather than a last-ditch effort.

The Future: A Holistic Approach to Breeding and Farming

Understanding this interplay between soil, microbes, plant hormones, and cellular processes like autophagy opens up exciting new avenues for agriculture. In the past, breeding focused almost exclusively on high yield under ideal conditions. Now, the goal is shifting towards "yield stability"—creating crops that can perform reliably even when conditions are tough.

By studying these natural resilience mechanisms, scientists can identify traits for future breeding programs. Perhaps we can breed crops that are better at partnering with PGPB, or that have a more efficient and well-regulated autophagy system.

The path forward isn't just about designing a "super plant" in isolation. It's about developing an integrated approach that considers the entire ecosystem—the soil's physical properties (improved by biochar), its living microbiome (supported by PGPB), and the plant's own incredible genetic and cellular toolkit for survival. By supporting plants from the soil up and understanding their internal recycling power, we can build a more resilient and sustainable food system for a challenging future.