Add your promotional text...

Siderophores Explained: Nature's Microscopic Fertilizers

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Timofeeva AM, Galyamova MR, Sedykh SE. Bacterial Siderophores: Classification, Biosynthesis, Perspectives of Use in Agriculture. Plants (Basel). 2022 Nov 12;11(22):3065. doi: 10.3390/plants11223065. PMID: 36432794; PMCID: PMC9694258. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

2/9/20264 min read

The Iron Paradox: Why Plants Can Starve in an Iron-Rich World

Iron is absolutely essential for life. In plants, it's a vital component for everything from photosynthesis (the process that creates energy from sunlight) to chlorophyll synthesis (what makes plants green). Over a hundred different enzymes that drive a plant's metabolism rely on iron to function. Without enough iron, plants become weak, their leaves turn yellow, and crop yields plummet – a major economic problem for farmers worldwide.

Here's the paradox: Earth's crust is full of iron. So why do plants struggle to get enough? Most of that iron is in the form of Fe(III), or "rust," which is incredibly insoluble in soil. Imagine trying to drink a rock – that's what it's like for a plant trying to absorb Fe(III). They need iron in a bioavailable form, and that's where some microscopic heroes come in: siderophore-producing bacteria.

Meet the Siderophores: Nature's Tiniest Iron Chelators

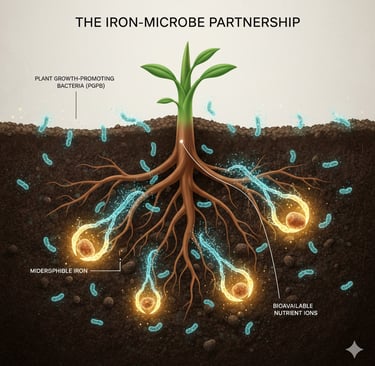

Living in the bustling ecosystem around plant roots (the rhizosphere) are countless Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB). Many of these bacteria have a remarkable superpower: under iron-deficient conditions, they synthesize and release tiny molecules called siderophores.

Think of a siderophore as a specialized molecular claw. These low-molecular-weight compounds have an incredibly strong and specific affinity for Fe(III). They are so powerful they can literally pull iron away from other molecules it's bound to in the soil. Once a siderophore latches onto an iron ion, it forms a soluble Fe-siderophore complex. Suddenly, the undrinkable "rock" of iron is transformed into a transportable "juice" that can be absorbed by the bacteria, and, crucially, can also be made available to the plant.

The Triple-Benefit of Siderophore-Producing Bacteria

These PGPB are not one-trick ponies. Their benefits for agriculture are manifold:

Direct Nutrition: By providing plants with accessible iron, they directly boost growth. Studies have shown that adding siderophores to soil along with iron leads to healthier, heavier plants compared to adding iron alone.

Bio-Fertilization: Many of these bacteria have other useful skills. Some can "fix" nitrogen from the atmosphere or solubilize phosphorus locked up in the soil, providing plants with the other essential nutrients they need. This makes them powerful candidates for creating holistic biofertilizers.

Natural Biocontrol: Siderophores are so good at scavenging iron that they can effectively starve out harmful plant pathogens (like certain fungi and bacteria) in the soil, which also need iron to survive. By locking up the available iron, beneficial bacteria can suppress diseases and protect the crop.

As the world's population grows and we face pressures on arable land, there is a strong push towards sustainable agriculture. Strategies like the EU's "Farm to Fork" aim to reduce our reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Microbial biostimulants, especially consortia of different PGPB, are seen as a highly promising, eco-friendly solution to improve soil fertility and plant resilience.

The "Who" and "What" of Siderophores

Scientists have identified siderophore-producing bacteria in dozens of genera, with Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Azotobacter, and Pantoea being some of the most studied and promising for agricultural use.

For instance, certain Bacillus subtilis strains help wheat plants grow better under drought and can make maize crops more resistant to disease. Pseudomonas species are well-known for producing a class of powerful siderophores called pyoverdines, which not only feed the plant but are also excellent at suppressing fungal pathogens. Nitrogen-fixing bacteria like Azotobacter and Azospirillum also produce siderophores, combining their iron-scavenging abilities with providing essential nitrogen to crops like cotton and corn.

Chemically, siderophores are diverse but are often classified by the functional groups they use to grab iron. The main types are hydroxamates, catecholates, and carboxylates. Many of the most powerful siderophores are actually a mixed type, combining several of these groups to create an exceptionally stable bond with iron.

The Life of a Siderophore: A Quick Tour

The process is a fascinating biological assembly line:

Biosynthesis: Inside the bacterial cell, siderophores are built by complex enzyme machinery. The three main pathways are Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase (NRPS), Polyketide Synthase (PKS), and NRPS-Independent Siderophore Synthetase (NIS). Think of these as different types of molecular factories that stitch together amino acids and other building blocks to create the final siderophore molecule.

Secretion: Once made, the siderophore (without iron, called an "apo-siderophore") is pumped out of the bacterial cell into the soil.

Chelation: In the soil, the siderophore finds and binds tightly to an Fe(III) ion.

Uptake: The Fe-siderophore complex is then recognized by specific receptors on the surface of bacterial cells and actively transported back inside.

Release: Inside the cell, the iron is released from the siderophore, either by a chemical reaction that changes the iron's charge (Fe(III) -> Fe(II)) or by enzymes that break down the siderophore molecule itself. The now-free iron can be used in the cell's metabolism.

How Do Plants Benefit?

The exact mechanism of how plants get the iron from bacterial siderophores is still being studied, but there are two main theories. Either the plant's root system can directly absorb the entire Fe-siderophore complex, or the iron is released from the complex near the root surface and then taken up by the plant's own transport systems. Either way, the bacteria do the hard work of making the iron soluble and bringing it to the plant's doorstep.

The Future is Microbial

The study of siderophores is crucial for the future of sustainable farming. While we know they work, there is still much to learn about the relationship between a siderophore's specific chemical structure and its effect on different plants. Further research into these mechanisms will help scientists create more effective "consortia" of beneficial bacteria, tailor-made to improve soil health, increase crop yields, and help us feed the world in a more eco-friendly way.