Add your promotional text...

Unearthing the Benefits of Cover Crops for Soil Microbes and a Cooler Planet

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Muhammad I, Lv JZ, Wang J, et al. Regulation of Soil Microbial Community Structure and Biomass to Mitigate Soil Greenhouse Gas Emission. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:868862. Published 2022 Apr 25. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.868862. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

10/6/20255 min read

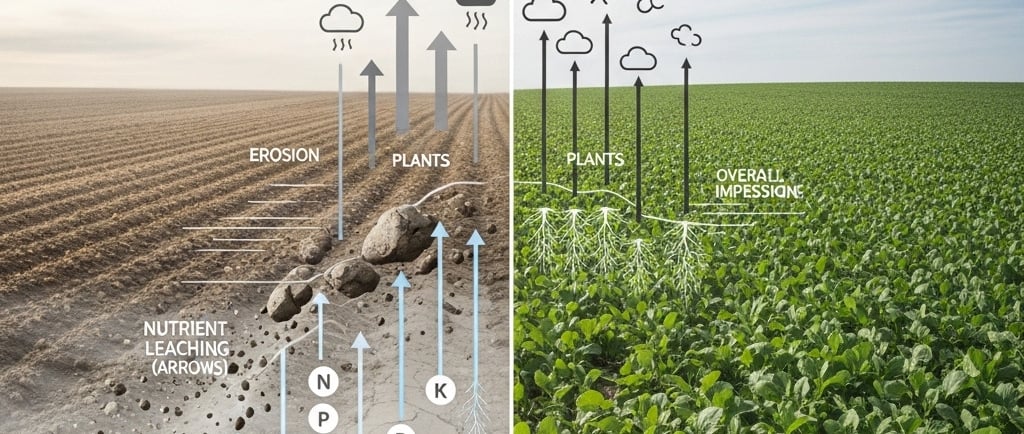

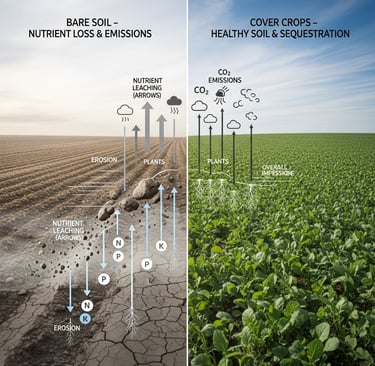

For decades, we’ve often left farm fields bare and exposed during the off-season. But what if this empty space is a missed opportunity? A growing body of research shows that planting "cover crops" during these fallow periods is a powerful tool to build healthier soils, reduce pollution, and even help in the fight against climate change by managing greenhouse gas emissions. These humble plants, grown not for harvest but for the soil itself, are revolutionizing how we think about sustainable farming.

What Are Cover Crops, and Why Do They Matter?

Cover crops are plants grown to cover the soil rather than for the purpose of being harvested. Think of them as a living blanket for farmland. After their short growing season, they are often worked back into the earth, acting as a "green manure." The benefits are immense:

They build healthy soil: Cover crops prevent soil erosion from wind and rain, improve soil structure, and increase the amount of organic matter, which is vital for fertility.

They manage nutrients: They act like sponges, soaking up excess mineral nutrients (like nitrates) left over from previous crops, preventing them from leaching into our groundwater and polluting waterways.

They boost biodiversity: They create a thriving environment for a huge range of beneficial life, from microscopic soil microbes to insects and birds.

They control weeds naturally: Many cover crops release natural substances (allelochemicals) that can suppress the growth of common weeds, reducing the need for herbicides.

At the heart of these benefits is a dynamic relationship between the cover crops, the soil, and the vast, unseen community of soil microbes. The type of cover crop planted and how it's managed directly influences soil carbon and nitrogen cycles, which in turn affects both soil health and the emission of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrous oxide (N2O), and methane (CH4).

The Cast of Characters: Legumes vs. Non-Legumes

Not all cover crops are created equal. They generally fall into two main categories, each with its own strengths:

Legume Cover Crops (LCCs) - The "Nitrogen Fixers":

This group includes plants like vetch, clover, and field peas. Their superpower is "fixing" nitrogen from the atmosphere and storing it in the soil, thanks to a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia bacteria.

Pros: They act as a natural fertilizer, reducing the need for synthetic nitrogen. Their residues are rich in nitrogen (a low C:N ratio), so they decompose quickly, making nutrients readily available for the next cash crop.

Cons: Because they decompose so quickly and are rich in nitrogen, they can sometimes lead to a short-term spike in nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, a potent greenhouse gas.

Non-Legume Cover Crops (NLCCs) - The "Carbon Builders":

This group includes cereals and grasses like rye, oats, and barley.

Pros: They are excellent at scavenging and holding onto leftover nitrogen in the soil, preventing it from leaching away. They typically produce more biomass (plant material) and are rich in carbon (a high C:N ratio). This makes them fantastic for building long-term soil organic matter and improving soil structure.

Cons: Their high carbon content means they decompose more slowly. This can sometimes temporarily "tie up" nitrogen in the soil, making it less available to the following crop in the short term.

Mixed Cover Crops - The "Best of Both Worlds":

Often, the smartest strategy is to plant a mix of legumes and non-legumes. This balances the rapid nitrogen release of legumes with the carbon-building power of grasses, often leading to a more stable C:N ratio that can reduce N2O emissions while still improving soil fertility.

Cover Crops and the Soil Microbial Universe

The real magic of cover crops happens at the microscopic level. A healthy soil is teeming with billions of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms that are essential for nutrient cycling and decomposition.

Feeding the Masses: Cover crops, both through their living roots and their decomposing residues, provide a massive food source for this microbial community. This boost in microbial activity and biomass is a cornerstone of improved soil health. Studies have shown that soils with cover crops have significantly higher microbial populations compared to bare fallow land.

Shifting the Community: The type of cover crop can influence which microbes thrive. For example, legumes can foster specific bacteria and fungi that are good at processing nitrogen-rich material. Grasses, on the other hand, can stimulate beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), which form vast networks that help plants access water and nutrients. Generally, cover crops lead to a more abundant and diverse microbial community, which is a key indicator of a resilient and healthy ecosystem.

The Greenhouse Gas Equation: It's Complicated

Farming is a significant source of greenhouse gases, and cover crops can influence these emissions in complex ways.

Carbon Dioxide (CO2): When cover crop residues decompose, soil microbes respire, releasing CO2. Generally, adding more organic matter (like cover crops) can temporarily increase soil CO2 emissions compared to bare land. However, this is part of a healthy, active ecosystem. More importantly, cover crops are also pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere as they grow and are a key tool for building stable, long-term carbon stocks in the soil (carbon sequestration), which is a major climate benefit.

Nitrous Oxide (N2O): This is a powerful greenhouse gas produced by microbes during nitrogen cycling. The impact of cover crops here depends heavily on the C:N ratio.

Low C:N crops (Legumes): Their quick decomposition and high nitrogen content can lead to short-term spikes in N2O emissions.

High C:N crops (Non-legumes): These can sometimes reduce N2O emissions by immobilizing nitrogen.

Mixed crops: Often provide a good balance, potentially mitigating the N2O spike from legumes.

Methane (CH4): Methane emissions are primarily an issue in flooded, anaerobic conditions, such as rice paddies. Adding any organic matter, including cover crop residues, to flooded fields can increase CH4 production by providing more food for methane-producing microbes (methanogens). The type of residue matters here too, with low C:N ratio crops often stimulating more activity.

Managing Cover Crops for Maximum Benefit

How a farmer terminates (kills) the cover crop before planting the main cash crop also plays a huge role:

Incorporation (Tilling): Mixing the residues into the soil puts them in direct contact with microbes, leading to rapid decomposition, quick nutrient release, and often a larger, faster spike in CO2 and N2O emissions.

Mulching (No-Till): Leaving the residues on the soil surface as a mulch leads to slower decomposition. This method is excellent for conserving soil moisture, controlling weeds, and can reduce N2O emissions compared to incorporation.

Roller-Crimping: A popular no-till method where a special roller flattens the cover crop, creating a thick mat of mulch.

Herbicides: Used to kill the cover crop, leaving residues standing. Can have mixed effects on soil microbes and GHG emissions.

The Takeaway: A Powerful Tool for a Sustainable Future

Cover cropping isn't a silver bullet, but it's a profoundly effective strategy for improving agricultural sustainability. While there are complex trade-offs to manage—especially regarding short-term greenhouse gas emissions—the overarching benefits are clear.

Cover crops enrich the soil with organic matter, foster a vibrant and diverse microbial community, reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers, and help prevent nutrient pollution. By choosing the right mix of cover crops (legumes vs. non-legumes) and using smart management practices (like mulching instead of tilling), farmers can optimize these benefits while mitigating potential downsides like N2O emissions. As research continues to unravel the intricate connections between plants, microbes, and our climate, cover cropping stands out as a key practice for building more resilient, productive, and environmentally friendly farms.