Add your promotional text...

Unlocking Nature's Superpower: How We Can Protect the Bacteria That Feed Our Plants

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Pereira JF, Oliveira ALM, Sartori D, Yamashita F, Mali S. Perspectives on the Use of Biopolymeric Matrices as Carriers for Plant-Growth Promoting Bacteria in Agricultural Systems. Microorganisms. 2023 Feb 13;11(2):467. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11020467. PMID: 36838432; PMCID: PMC9963413. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

1/16/20263 min read

A Growing Challenge for a Hungry Planet

Our world faces a monumental task: feeding a growing population amidst a changing climate. Events like pandemics and global conflicts have shown how fragile our food supply can be, and the environmental toll of conventional agriculture is becoming increasingly clear. Climate change brings more extreme weather—droughts, floods, and heatwaves—that stress our crops, degrade our soil, and threaten water supplies.

For decades, the answer was often more chemical fertilizers and pesticides. But this approach can be harmful to the environment and unsustainable in the long run. The question becomes: how can we improve crop productivity and ensure food security for generations to come, while also protecting our planet? The answer may lie with some of the smallest organisms on Earth.

Nature's Allies: Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB)

Living in the soil, especially in the bustling zone around plant roots known as the rhizosphere, are countless non-pathogenic bacteria. Many of these, called Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria (PGPB), have a remarkable, mutually beneficial relationship with plants.

These microscopic powerhouses act as natural biofertilizers and biopesticides, helping plants in numerous ways:

They provide nutrients: PGPB can "fix" nitrogen from the air or unlock phosphorus in the soil, making these vital nutrients available to the plant.

They produce hormones: They synthesize plant hormones like auxins that stimulate root growth, helping plants access more water and nutrients.

They reduce stress: Some PGPB produce an enzyme (ACC deaminase) that lowers a plant's stress hormone levels, helping it stay healthier under tough conditions like drought or high salinity.

They protect against disease: They can produce compounds that fight off harmful pathogens, acting as a natural defense system.

By harnessing PGPB, we can create eco-friendly "inoculants" to improve plant health and productivity, reducing our reliance on synthetic chemicals.

The Delivery Problem: Helpful Bacteria Need Protection

So, if these bacteria are so great, why aren't they used everywhere? One of the biggest challenges is ensuring they survive the journey from the lab to the field. When simply sprayed on seeds or soil, these beneficial microbes are exposed to harsh conditions like UV radiation, temperature swings, and competition from other soil life. Many don't survive long enough to establish themselves and help the plant.

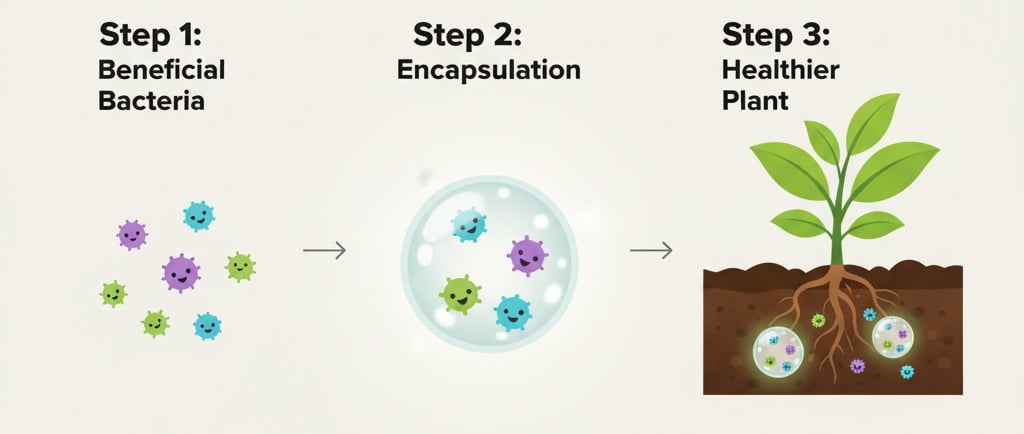

This is where a clever solution comes in: encapsulation.

Smart Pods: Biopolymers as Tiny Life Rafts for Bacteria

Scientists are developing ways to protect PGPB by encapsulating them within tiny matrices made of biopolymers. These are natural, biodegradable materials from renewable sources, like seaweed, corn, or crustacean shells. Think of it as creating tiny, protective "pods" or "life rafts" for the bacteria.

This process of immobilization protects the bacteria from the harsh environment, prolongs their shelf life, and allows for a controlled, gradual release of the microbes right where they are needed – near the plant's roots. Some of the most promising biopolymers being studied include:

Alginate: Extracted from brown algae, this is the most studied material. It forms a gel-like bead when mixed with calcium, trapping the bacteria inside a porous, protective matrix. Studies show bacteria like Azospirillum brasilense can survive for over a year inside these alginate beads, ready to go to work when applied to soil.

Starch: A very low-cost and widely available biopolymer from sources like corn or cassava. While not as strong on its own, starch is often blended with other materials (like alginate) to improve the protective beads, making them more resistant to physical stress and UV radiation. It can also act as a food source for the encapsulated bacteria.

Chitosan: Derived from chitin (found in shrimp and crab shells), chitosan is not only a great carrier but also has its own beneficial properties. It can help plants defend against pests and diseases and even improve the soil's water retention.

Gelatin: A low-cost protein that can also be used, often in combination with other biopolymers, to create effective protective microspheres for PGPB.

The Future is Encapsulated

The use of biopolymeric matrices to deliver PGPB is a huge step forward for sustainable agriculture. These innovative biofertilizers and biopesticides can help maintain soil fertility, improve crop productivity, and reduce our reliance on harmful chemicals.

While much of the research is still in development, the results are incredibly promising. The next major step is to scale up production of these encapsulated microbes and conduct more large-scale field trials to confirm their effectiveness under real-world farming conditions. By perfecting the "delivery system" for these tiny natural allies, we can unlock their full potential to help us grow food more sustainably for a healthier planet.