Add your promotional text...

Unseen Helpers: Tapping into the Power of Plant-Microbe Partnerships

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Laishram B, Devi OR, Dutta R, Senthilkumar T, Goyal G, Paliwal DK, Panotra N, Rasool A. Plant-microbe interactions: PGPM as microbial inoculants/biofertilizers for sustaining crop productivity and soil fertility. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2024 Dec 16;8:100333. doi: 10.1016/j.crmicr.2024.100333. PMID: 39835267; PMCID: PMC11743900. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

12/26/20254 min read

The Challenge of Feeding the World, Sustainably

Our planet faces a monumental task: feeding a rapidly growing population while protecting the environment. For decades, intensive agriculture has relied heavily on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. While these have boosted yields, they've come at a cost – chemical pollution, environmental degradation, and potential health risks. At the same time, climate change is throwing new challenges at farmers, from extreme heat and flooding to severe droughts, all of which threaten crop productivity.

So, how can we intensify agriculture to ensure food security without further harming our planet? The answer might be hiding right under our feet, in the microscopic world of the soil. A vast and diverse community of microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, and more—interacts with plants in a complex dance. Some are harmful, but many are incredibly beneficial. Scientists are increasingly turning their attention to these tiny allies, known as Plant Growth-Promoting Microorganisms (PGPM), as a powerful, natural tool for creating a more sustainable and resilient agricultural future.

Part 1: What is the Plant Microbiome?

Every plant, from a tiny weed to a towering tree, is a bustling ecosystem. It hosts a community of microbes on its leaves and stems (the phyllosphere) and, most importantly, in and around its roots (the rhizosphere). This entire community is the plant's microbiome. These microbes can be:

Epiphytes: Living on the plant's outer surface.

Endophytes: Living inside the plant's tissues without causing disease.

The rhizosphere is the real hub of activity. It's the thin layer of soil immediately surrounding the plant's roots, and it's teeming with life. This is where the magic happens. Plants release a cocktail of sugars, amino acids, and other compounds—collectively called root exudates—into the soil. This isn't waste; it's a deliberate invitation. These exudates act as signals and food, attracting a specific community of microbes to the root zone.

In this dynamic environment, a plant essentially "farms" its own microbiome, encouraging beneficial microbes to stick around while sometimes repelling harmful ones. It's a two-way street: the plant provides shelter and food (carbon from photosynthesis), and in return, the beneficial microbes provide a host of services that are vital for the plant's health and growth.

Part 2: The PGPM Toolkit: How Microbes Help Plants Thrive

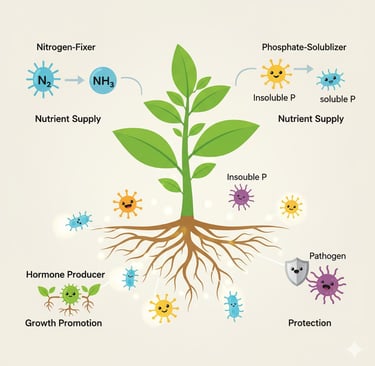

Beneficial microbes, or PGPM, aren't just passive residents; they are active partners with a diverse toolkit. They help plants in two main ways: direct and indirect.

Direct Mechanisms (Growth Promotion):

Biofertilization: Many PGPM act as natural fertilizer factories. They can "fix" atmospheric nitrogen, converting it into a form plants can use. Others can solubilize minerals locked up in the soil, like phosphorus and potassium, making these essential nutrients available for root uptake.

Phytohormone Production: PGPM can produce plant hormones like auxins (which stimulate root growth), cytokinins, and gibberellins. This hormonal boost encourages stronger, more extensive root systems, allowing plants to access more water and nutrients.

Indirect Mechanisms (Protection & Stress Relief):

Biocontrol: PGPM can outcompete harmful pathogens for space and nutrients. They can also produce antibiotics or enzymes that attack and suppress disease-causing microbes, acting as a natural shield.

Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR): Inoculating a plant with certain PGPM can prime its immune system, making the entire plant more resistant to future attacks from a wide range of pathogens. It's like giving the plant a vaccine.

Stress Amelioration: PGPM help plants cope with environmental (abiotic) stress like drought, salinity, and heavy metals. They can produce compounds that help the plant manage water balance, reduce levels of harmful stress hormones (like ethylene), and produce antioxidants to fight cellular damage.

Part 3: From Lab to Field: PGPM as Biofertilizers

The ultimate goal is to harness the power of these microbes to create "microbial inoculants" or "biofertilizers." These are products containing live, beneficial microorganisms that can be applied to seeds, soil, or plant roots to boost crop performance.

The process involves:

Isolation & Screening: Scientists find promising PGPM strains, often from harsh environments where microbes have evolved to be tough.

Characterization: They test these strains in the lab to see what beneficial traits they have (e.g., nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization).

Formulation: The microbes are mixed with a carrier (liquid or solid) that helps them survive, stay stable, and be easily applied by farmers.

Field Trials: The most promising formulations are tested in real-world greenhouse and field conditions to ensure they are effective.

While single-strain inoculants have been used for decades (especially Rhizobium for legumes like soybeans), the future lies in microbial consortia—carefully selected teams of different microbes that work together synergistically to provide a wider range of benefits. Researchers are even designing "synthetic communities" (SynComs) to create optimal microbial cocktails for specific crops and conditions.

Part 4: The Future is Microbial

The market for biofertilizers is growing rapidly as the demand for organic food and sustainable farming practices increases. However, there are still hurdles to overcome. The effectiveness of an inoculant can vary depending on the climate, soil type, and existing microbial community. Regulatory frameworks also need to adapt to this emerging technology.

Despite these challenges, the path forward is clear. By leveraging advanced technologies to understand the complex interactions in the rhizosphere and by designing more effective and stable microbial products, we can unlock the full potential of PGPM. These unseen allies offer a powerful, eco-friendly way to enhance soil fertility, protect plants from stress and disease, and ultimately help us sustain crop production for generations to come.