Add your promotional text...

Wastewater's Plastic Problem: A Contaminant Cycle You Need to Know About

Source & Further Information: The findings and concepts discussed in this article are largely based on the research presented in the following scientific paper: Koyuncuoğlu P, Erden G. Sampling, pre-treatment, and identification methods of microplastics in sewage sludge and their effects in agricultural soils: a review. Environ Monit Assess. 2021 Mar 10;193(4):175. doi: 10.1007/s10661-021-08943-0. PMID: 33751247. We encourage readers interested in the detailed methodology and complete results to consult the original publication.

10/24/20253 min read

The Unseen Journey of a Plastic Fiber

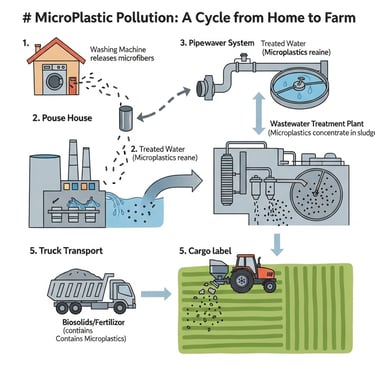

Imagine a tiny fiber shedding from a fleece jacket in the washing machine, or a microbead from a face wash going down the drain. We rarely think about where these tiny plastic particles go next. The answer, surprisingly, is often a journey that ends in the very soil used to grow our food. This is the hidden story of microplastic pollution, and wastewater treatment plants are at the heart of it.

Plastics are everywhere – durable, cheap, and incredibly useful. But their longevity is also their curse. In the environment, they don't disappear; they just break down into smaller and smaller pieces. When these particles are smaller than 5mm, we call them microplastics. They've been found in oceans, rivers, and even the air we breathe. But one of the biggest, yet least discussed, pathways for microplastics into our environment is through our own wastewater systems.

The Wastewater Trap: Concentrating the Problem

Wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are modern marvels, designed to clean our water before returning it to the environment. While not specifically built to catch plastics, they are remarkably effective at it, removing over 95% of microplastics from the water they process.

But this creates a new problem: the plastics don't vanish. They are simply transferred from the water into the solid byproduct of the treatment process – a dense, organic-rich material called sewage sludge. The result is that this sludge becomes a highly concentrated soup of the microplastics that were once diluted in millions of gallons of wastewater.

From Treatment Plant to Farm Field: The "Biosolids" Pathway

So, what happens to all this sewage sludge? In many countries, it's treated further to kill pathogens and stabilize organic matter, at which point it's often renamed "biosolids." These biosolids are rich in nutrients and are widely used in agriculture as a cost-effective fertilizer to improve soil fertility. It's a form of recycling that returns valuable organic matter to the land.

This is where the hidden loop closes. By spreading biosolids on agricultural fields, we are unintentionally seeding our soils with enormous quantities of microplastics. Studies have shown that fields treated with biosolids have significantly higher concentrations of microplastics than untreated fields, and the plastic accumulates over time with repeated applications. While the ocean is often seen as the ultimate sink for plastic waste, some estimates suggest that far more plastic (4 to 23 times more) is released onto land each year.

More Than Just Plastic: The 'Hitchhiker' Problem

The issue gets even more complex. Microplastics in the soil aren't just inert, tiny pieces of litter. Due to their large surface area and water-repelling nature, they act like tiny sponges for other pollutants present in the wastewater or soil.

These plastic particles can attract and bind with a cocktail of other contaminants, including:

Heavy Metals like lead, cadmium, and arsenic.

Antibiotics and the antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) that are common in sludge.

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) like pesticides.

When these "pollutant-loaded" microplastics are introduced to the soil, they create a combined threat. They can alter the soil's physical properties, affect water relationships, and act as a carrier, transferring these harmful hitchhikers into the soil ecosystem.

Ecological Risks: What's Happening Beneath Our Feet?

The presence of this microplastic "cocktail" poses a significant, though still not fully understood, risk to soil health. Research has shown that:

Soil Organisms are Affected: Earthworms, which are vital for soil health, are known to ingest these plastics. Studies have observed adverse effects like surface damage, oxidative stress, and even DNA damage in earthworms exposed to microplastics.

Microbial Communities Change: The vast community of bacteria and fungi that keep soils healthy can be disrupted. Microplastics can alter the activity of soil enzymes and change the nutrient cycles that plants depend on.

Plants Can Be Impacted: There is growing evidence that plants can be affected by changes in soil properties and may even take up the smallest plastic particles (nanoplastics). This could inhibit water uptake, alter nutrient absorption, and potentially introduce plastics into the food chain.

The Scientific Challenge: A Murky Picture

One of the biggest challenges for scientists is the lack of standardized methods. Studying microplastics in a complex, organic-rich material like sewage sludge is incredibly difficult. Researchers use a variety of chemical and physical methods to dissolve the organic matter and separate the plastics, but these methods vary from lab to lab, making it hard to compare results. Identifying the tiny particles as actual plastic often requires advanced and expensive spectroscopic techniques, as simple visual identification under a microscope is notoriously unreliable.

Despite these challenges, the evidence is clear: our wastewater systems are a major pathway for concentrating microplastics, and the agricultural use of biosolids is a primary route for introducing them into our soils, with unknown long-term consequences for soil health and food safety. More research is urgently needed to understand these risks and develop safer ways to manage our waste.